Facts

What's it About?

Spoils/Treasure is a series of short stories in which the same things happen. An elf dies, an object they loved is retreived by an orc, and the orc loves it as well, but for a different reason.

Rating

Mature, I suppose/

How's it weird?

It's about orcs. That's weird enough. It's also in an 'orcs are people' tradition of writing and the further 'orcs are elves' subgenre that not everyone loves.

AO3 link?

You know it.

SPOILS/TREASURES

--

Original Note:

In the masterful science fiction series Imperial Radch by Ann Leckie, the titular Radch society has exactly one personal pronoun in their language, which is rendered as 'she' in English. Similarly, in the fic below, the orcs use only one personal pronoun regardless of bodily composition or personal identity, which is 'he'. They all use 'he' no matter what. This is supposed to indicate that in the language they are using (one that I write as having been issued to them by their Maiar authorities) there is only one way to refer to themselves and each other. The fact that this default pronoun is 'he' instead of something else is just a whole other thing, though, isn't it.

--

...and his banner, blue and silver, they trod into the mire of his blood.

Blue.

Iluk had never had anything blue before.

Most of the other kin could not see blue. Such things depended on where a kin’s family was created, how old his line was, which fortress he was made in.

Iluk’s family was first made in Utumno in older days. He was not that old himself but the old blood he was born with had the sight of colors in it, a weakness to touch in it, a slowless in the mind that made them sometimes unreliable in battle. Other kin, made in Angband or Tol-in-Gaurhoth, had sharper senses of scent, more tolerance to the heat or the cold; they were not known for wandering off in old age, addled and grumbling, frightened to die in battle like Iluk’s kin were. Iluk watched his elders grow slow and hesitant as the years pressed on them, turn inward and grow quiet.

Iluk’s old blood saw blue. Many feet belonging to those younger clans, those stronger clans, had already trod over the blue fabric now half-buried in the mud, unaware that it wasn’t grey or brown or whatever muted colors their duller eyes could see. They had so many things that Iluk did not, and with those powers had taken many things from him, the blades and tools he would rather keep, the solitude he might otherwise enjoy, the heirs he bore them and gave away, but sometimes he won things back by telling a kin that he would reveal to him what color his eyes were, what colors his bed-mates’ eyes were, bargaining that information to put his things back in his hands.

Iluk had blue eyes, flame-blue, vein-blue. He kept to himself the information that that color was uncommon. The old blood cut through, springing up blue in his eyes; blue was a rare color, only speckled as if by accident across green fields and valleys, and it wilted first when the kin came to make the land black and grey. Blue was unseen among the stars except as whitest blue, unknown in the rivers and lakes except in the spring’s most deathlike calm; its only stronghold was the sky in the day, which was grey to the eyes of most kin.

Iluk knew it was blue. His eyes were blue. The banner soaked with blood at his feet was blue.

He bent down and gripped it in his fist. As he pulled it up, clods of mud broke and fell, elven limbs rolled away. Even among finery-armored elves was blue rare; the gold-tipped hoard they had conquered with fire had been wearing red or black or green or brown before they were made black, but not blue, not except for a few. From crafting armor for his own kin Iluk knew that any color but brown or white or gray meant waste. The cloth in his hands then was rare and valuable, even valuable to wine-drinking elves, and no one now knew except him.

The thought of portioning and selling it drifted through his head, insistent, alluring, surely correct. Iluk needed good spoils to barter against bets, against extortion, against domination; when men of younger kin came hunting, he needed things he could offer other than his body, because he hated having children. But though he needed that hoard very badly and though it was by far the most correct choice to use that thick, fine, slick-feeling, strange fabric for that security, Iluk finds himself abandoning that correct thought quickly. Incorrectness was another trait common to his thin old blood.

They won’t know it’s blue. They will feel its quality, its toughness against the wind, the strength it once used to snap in the gale as it was raised on horseback above the heads of the charging steeds, but they won’t even know as they take it from his hands that it is blue. Iluk does. He could see it. A deep blue, a dark blue, so rich he struggled to think of what to compare it to. The stones that the Masters wore when they took moral form. The sky when night has almost risen. The marbling of veins on freshly-cut intestines, throbbing with dark blood.

Iluk saw a tunic in his mind. It would go all the way down to his knees, and peek out like slit eyes from the belted leather above it. Or it could be folded over itself to make quilted armor, there was just enough; its star-spangled design would glimmer like moonlight on a running river. Gloves to put under his gauntlets, so he could look down and see the blue between the joints, slivers as thin as the first fingernail of dawn on the horizon.

Which was red, sometimes. Clay red, fire orange, corpse white. As many colors as the body in the stages of mortification, flushed and then pale and them blossoming with crocus and hyacinth and violets in shaded patches, and sometimes Iluk was in such company that he alone knew what color the dawn was, seen only in moments when he dared to turn his head, look away form the march, and see the white sun inflaming the sky around it like burning houses, shaming the earth beneath it with a scarlet flush.

Another kin, Iluk realized, was shuffling up to him, standing at his shoulder. Iluk glared a brief warning at him, though he hoped he wouldn't have to back that warning up.

The kin came up to him anyway. “That is a good spoil,” he said of the banner in Iluk’s hands.

That meant that he expected Iluk to give it to him. This one was tall and strong, likely born of one of Lord Sauron’s clans, and surely he had close kin and indebted ones he could call him to put steel to his demands, for he was bold.

“It is,” said Iluk, and, in spite, “you see well.” Then, looking down, he reached up and took the very helm from his head. “This, I thought, was good as well; do you like it?”

The kin laughed at him. That was correct of him; it was pathetic that Iluk was willing to bargain armor to keep his muddied banner. He snatched the helmet up and told Iluk to enjoy his cloth for as long as he held it.

Iluk kept his eyes on it as the kin walked away again. The blood was slowly dripping out of its strangely woven tresses; the folds in his hands increased as he pulled all of it out of the ground. As earth and gore dripped away, the silver stars, stitched in with knots as tiny and tight as grains of sand, slowly began to shine again.

One elf had had his skull flattened into the banner. Iluk picked shards of it out of the threads and marveled that they had been little hurt despite the many threats of the shattered bone. It was even greater and wider than it had looked while half-buried; he wrapped it around and around his fists. Perhaps he could make both the tunic and the quilted armor. A full outfit, all blue, like he had pulled down the sky to clothe his limbs, and he alone would know, able to see the flashes like leaping fish between joints of armor and rings of mail, thin but bright, so quick that he could only catch them with his old-blood eyes.

He had never had anything blue before.

--

Original Note:

--

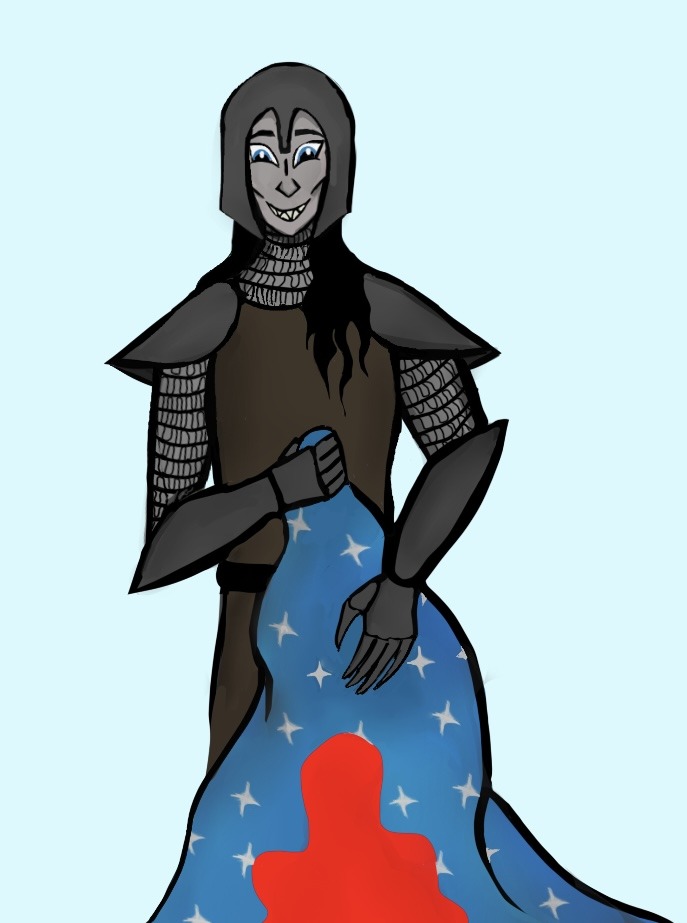

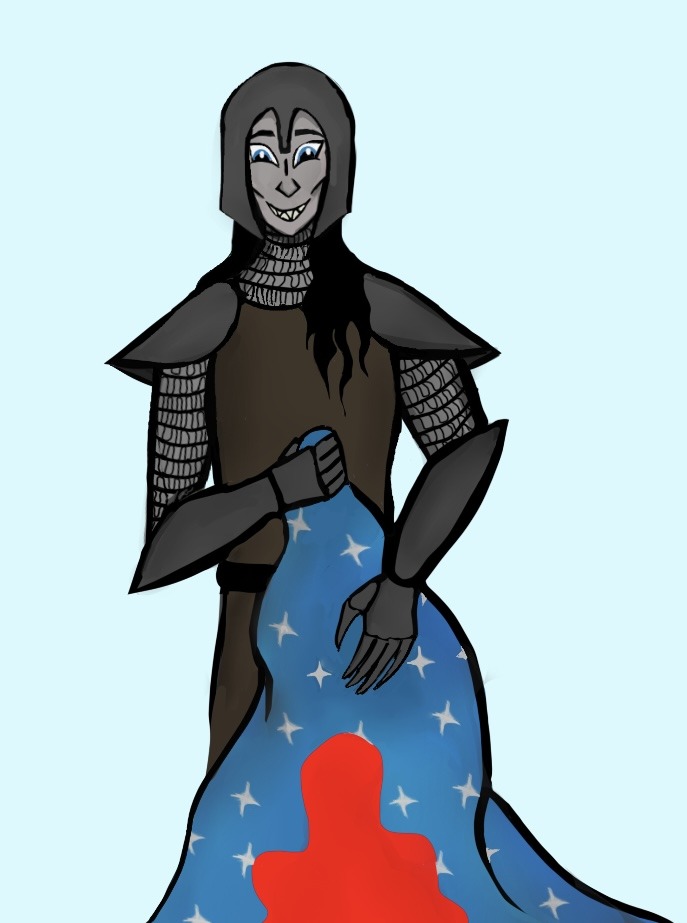

The talented and kind-hearted Destiny Minnow drew my Iluk! Here he is:

For this chapter, my use of colors was slightly inspired by John Carey's article about the perception of color in pre-modern Ireland (The Three Sails, The Twelve Winds, and the Question of Early Irish Color Theory) where, among other things, he posits that 'blue' and 'green' were perceived was one color, which was also 'gray' and 'black', but that there were several words for this one color actually differentiated by how light/dark and clear/muddy it was. Cross-reference the wine-dark sea; there are lots of examples of pre-modern cultures seeing the boundaries between colors very different from what is considered standard now. I was reading that article because I've been really into Echtra lately, but, you know, those wires get crossed... Anyway I just like Carey's work a lot and wanted to recommend him.

...his body as it fell smote the rocky slopes of Amon Gwareth thrice ere it pitched into the flames below.

The victorious kin dropped themselves into a frenzy of enrichment and pleasure on the ruins of the elven city the likes of which Teug had never seen before. Their hedonism even after the Battle of the Dragons was bested.

He stood at watch, for a while, observing the claiming and reclaiming from a dislocated doorway near the pinnacle of the city. He felt a dull pleasure while watching his men pull bone from bone out of the erstwhile elven King, splitting his knucklebones among them to be prized in fortune-telling sets, snapping his skull from his jaw for individual trophies, cutting off his thick braids to be bracelets, gifts for bed companions. The vision of what had once been a great Lord being torn apart into giblets and liquids filled Teug’s guts with warmth inside in a way that the rest of the reclaiming did not.

But the high sunlight above the mountains throbbed on the awful white stones all around him, glinting on the broken teeth of elven palaces and towers. It hurt his head through his eyes; the screams and whines grew thick in his temples. He relieved himself of duty (his subordinates would do whatever they wanted now no matter what he said or did) and began to descend the cracked streets of the city.

Teug had been promoted to his high position in the army because of the traits which made him otherwise unpopular. He never enjoyed gambling, pillaging, rampaging, raping; he followed orders when a human village or elven grove had to be destroyed and typically very well. He enjoyed battle itself, but the revels afterward made him testy and disagreeable. He would not do anything for a bribe or a favor or for anything at all except an equal exchange and this firmness had made him many enemies. It had also enabled him to destroy those enemies and thrive himself, as he could not be made to feel beholden or indebted to anyone by any tricks or attempts at twisting his guts through his heart. He did not feel the reaction to pleading or intimidation that he observed others having. He felt little, in fact, except pride in his position, comfort and stillness when he knew it was secure, and fierce joy when he overcame a challenge to that security. He was mocked nearly every step of the way as he descended the many winding steps of the city and left the post-battle celebrations behind him, but he did not feel the urge to join them, had never enjoyed it when he forced himself to, and at this age accepted he never would feel whatever excitement compelled his kin to bend themselves over corpses.

Teug left the crown-like white city through its now-shattered front gates, watching with appreciation the gentle smoke coiling up from dampened fires below. He had intended to just stand at the gates and wait through the night on a self-imposed watch, but the behavior there was exactly the same as above and nearly as loud. A man approached him with an offering; Teug enjoyed his position again as he grabbed his neck and choked it closed.

The man hadn’t done anything incorrect, but when Teug became aggravated like this, death briefly soothed his anger. He had worked hard and committed acts against his will to reach a position of prestige where he could do such things without repercussions, and he knew the relative worth of the bodies he now disposed of for his own contentment.

Contentment, he thought, leaving the body behind him and walking down not white steps but grey, outside of the city and carved into what was once a mountain-side before the tower-lust of the elves had caused them to break it. He rolled the word around in his head.

He liked words; this affiliation he kept to himself, because he had intuited in the few times he used words as it pleased him that the Masters did not like him to do so. They had their own languages, quick, sharp to the ears, as varied as rushing rivers; Teug could tell they had many words that they kept to themselves, leaving the kin only enough to summarize. (When he had reasoned that the Masters had made all of the kin’s words and gifted them the ones they saw fit for them to have he was not sure; it felt as though he had always known that and always known better than to mention it.) Contentment rolled in his head like a pebble scraped up by his boots bounced down the mountain stairs, its parts detaching from each other. He heard good in one part, inside in another.

He had realized a long time ago that complex words were made of simpler words, like great hordes being made of companies and bands, held together by social connections and correct command; the Lords who had made their words had done so with skill and art, and someone who knew the secrets of words could made more themselves, express things previously locked within. Teug had made words for himself that he only said in his head, repeated over and over. Earcuts, which were noises that hurt; this was one of his first, which he had made when he was still quite young. Calmcursive , the act of doing things in circles until he felt soothed. Illdulged , when a kin too much indulged himself and hurt himself with what he thought was pleasure. Teug never illdulged.

Teug did not mean to descend as far as he did, but he was being calmcursive and repeating an action which pleased him, walking down and down, as stone steps became dirt, mountain hill, then valley. The mountain and its ruins now stood high above him, burning, sometimes vomiting its bodies or stones down to the valley beneath him. In the shadow of the city, even on fire, the valley was deep and dark; Teug felt pleased, so he continued descending.

He sought the bottommost point and found when he arrived that it had already become full of refuse and rubble and bodies, covered by the ashes from a quick, hot fire that had been stifled by their cold, wet weight. Though he had hoped to find some deepest darkness, untouched earth, in that cold nadir, something about the silence of the corpses also pleased. The noise and grabbing and disruption all stilled, pressed together like seeds inside a pod. Here were kin and elves alike no different from fish in the river, drifting, disturbing nothing; reduced, they would all cry, but to him they were all made better, stripped of requests and demands and, to his eyes, made content.

He walked by the seam of bodies, but as he walked he thought he heard something. A voice; it mumbled, voice low and circular, rising and falling with the same repeated noises. Teug thought at first it must be someone crouching in the bodies, a fallen warrior dying in the heap or someone gone split-headed, hit out of their senses in battle and wandering. He brought his axe to bear and advanced on the noise, but as he approached, he saw none moving, not even fitfully on the ground.

He reached the point where he had to be standing right over the voice, but still, he saw none alive. Could there be a survivor buried beneath, someone who had barely survived a hard fall? As he listened, he became aware that it was an elf-tongue being spoken; surely no soft-bodied elf had survived the fall from the mountain. Uncertain, Teug used the heel of his boot to disturb the place where he heard the voice.

It rose in a flurry, speaking rapidly. New words, many; Teug heaved his axe high, but nothing moved. He watched, eyes flicking, but spied nothing. Yet the voice had to be right below him, and it had reacted to him.

“Speak right,” he snapped. For a moment, the voice was silenced. When it came up again, it still spoke elf, now at a conversational volume, surely trying to address Teug, but lacking the words.

Teug knelt down. He distressed the piled corpses with his foot again. The voice reacted just as it did before, but Teug could not understand anything it said except for one word. He picked it up in repetition; ‘Uruk’, the elf word for kin.

This he had heard enough times to pick out, like some paltry few other trips of the elven tongue. He knew when they called for advances and retreat and had ordered maneuvers around them with that knowledge before. So it was an elf that spoke, but where?

The corpse closest to Teug’s foot was an elf. He had been richly dressed in dark robes before his bones had been snapped by what must have been a fall from the walls high above. The corpse itself was wet and soft, destroyed utterly; this one was not alive. There was yet elven gold on his fingers, clinging to his broken skull with his braids, around his forehead, and tied in ribbons into a leather belt that held a sheathed sword.

Teug pressed his foot on his wounds for a reaction, but predictably, there was none. He tested that crown for some trick or magic, but there was nothing; he lifted the sword in its sheath and it burst in noise.

He couldn’t believe it, but he lifted the blade up, then down, and up again with his toe and the voice moved with it. Could it be? Teug dropped to his knees, minding not the cold corpses, and fixed his fingers to the belt on the corpse’s waist. The knot befuddled his fingers but the softened bands yielded easily to his axe (as did the gorey elf beneath, but it harmed him little now.) He freed the sword and scabbard and lifted them to his face, marvelling at how the voice went with the blade. Neither was damaged by the fall, either; it was as though the body of the elf had bent to cushion them, or else it had somehow had the wit to maneuver itself to avoid every strike of the long fall.

Teug turned it around in his hands, eyes watching, ears delighted. The flow of elven words was never-ending, like a man in panic, begging for his life. It did not repeat like a ghost but declared words like a Master, with many numbers of them at its disposal. Teug did not know what it was saying, but the more he listened, the more delighted he was. The sword spoke; just like kin, just like an elf or man, with the hot fire of life animating the air in his throat.

“Listen,” he told the sword, “and hear me the first time.” He did not think it understood, but it did fall silent. “I have captured you. You are my spoil. A spoil beyond spoils, I think; a master-spoil. Any kin would envy me, but none will have you unless he breaks my body.” Teug was not worried that any kin would dare challenge him, even for such a find; if anyone dared, Teug would win the challenge. It was the Masters he was worried about, the undying commanders who claimed every spoil with power or trickery in it. That Teug would not stand, so he would have to be clever about how he managed it. “You are in my power; see?”

He pulled the sword from his sheath, and went to bend it over his knee to frighten it (and thus to begin the process of controlling when it spoke and when it was silent), but was astonished; he could not bend the strange metal, not even slightly. It was ash-dark, and shone, and was harder than steel.

What it did do was complain, and that mightily, at the mishandling. Teug held it at arm’s length, impressed. He listened to the ongoing tirade, ears focused on the words, trying to find one he knew, something he had heard ringing across battlefields before.

Finally, he did. “Lord,” he repeated, testing the word on his tongue. He often repeated the elf-words to himself, but only silently. It was a word that meant ‘general’, he believed.

The sword was silent for a moment. Then, clearly testing, it repeated ‘Lord’, then a word. It did so a few times.

Teug repeated, to show he followed. “Lord Eol,” he said. What was this word? It followed ‘general’, was it another part of the title? A name? The broken body that laid at his feet now, did ‘Eol’ signify it?

The sword said some things; Teug did not know them. “Listen,” he said again.

“Listen”, it repeated.

Teug smiled.

–

Teug spent all the night in that valley, with the corpses that slowly grew cold and the sword in his lap. It has a tongue-twisting elven name, Anguirel. It could see, it seemed, so Teug could indicate things for it to name; with exhausting effort Teug had slowly picked out words from its hoard to add to his own, about a dozen in the night.

Gonn, gond, and sarn, all for stone. Megil , which meant sword, and galvorn , the metal this one was made of. Mor, duath, and dur, which all meant dark; all different words, with slight, sneaky variance, for types of darkness that did not fit into categories he recognized. Daen was corpse, that corpse was Maeglin or Melna . The night was du and his moon was ithil; it was also tilion, perhaps in another phase. Thin, now, it was curon, just like the blade, a metaphor that Teug recognized with cutting exactitude, because he had heard and admired the same concept of the bright, sharp blade-moon on the Masters’ tongues.

He learned also dern, which meant tough, and taug , which meant firm. Anguirel knew enough already to call him both.

Taug sounded so alike to the word he was named for. The coincidence stuck to him like blood that seeped through cloth, bothering his back just enough that he couldn’t dismiss it from his mind completely even as he walked from it.

He would have to keep these words locked away in the trunk of his skull so judiciously they had no chance of escape. He knew the Masters would not stand for it, in the same way he knew they had made all of the kin’s words, in the same way he knew, though he knew not how, that they were for some reason jealous of words and did not like sparing them.

Why? Teug could only assume it was for the same reason that they were jealous of such fine finds as Anguirel, of pilfered gold, of elven weapons and jewelry, of captives who had been powerful before dominated. Because they were greedy.

So was he.

--

Original Note:

--

GENEROUS use of parf edhellen in this story. It's a good thing that Sindarin is being approached by a complete beginner who doesn't understand its grammar or the culture that formed it at all here, because it makes my clunky use of Sindarin word-roots as stand-alone nouns representing rough concepts more excusable -u-

I am just so obsessed with Eol's talking swords now, I haven't gotten over them since writing the Curufin/Eol thing and I don't think I will. What is it? Is it itself? An extension of its maker? Is Anguirel a person? If so, how? If not, what? By the rules of this world, a constructed thing like a sword shouldn't be, made by a mastersmith or not. In an orc hand, in an odd way, it feels in place.

One last note: FWIW, this chapter of this fic is what has now made this an AO3 account with one million uploaded words. Woo!

...The sons of Finarfin bore most heavily the brunt of the assault, and Angrod and Aegnor were slain...

Gris’ throat complained louder than his knees. That was one of the bargains he had made with his slowly corroding body years ago. Every time the joints between his bones started grinding hard he cursed louder than they did, and that was the price everyone around him paid for making him do the hard work again.

The son of his old bed-mate (though he and Yin did not take their rests together any longer and the boy’s sire was another kin) cowered on the ground. Khiris had quick hands, always fiddling with something, doing and undoing knots, which was why Gris had reluctantly agreed to take a final apprentice—final, he insisted, because he knew and everyone knew he was nearly impossible to work with anymore, stoop-backed and snarling with every strike of the hammer as the very bones in his fingers fought against him.

Personally, he thought Khiris’ father had a load of wet shit in his skull, hooves on his wrists, and a wit as dull as a grandsire’s axe, which he had told Khiris many times. Khriris, warned extensively that if he pushed Gris too hard (or at all) he was likely to lose the final apprenticeship to one of the preeminent smiths of his dwindling generation, was forced to stew the insults in his gut. Gris thought it not impossible he was honing the boy who would murder him some day, but it was about fucking time someone did.

Good for Yin for feeling up to breeding at their age, but this was the last of his brood Gris would do anything for.

“KHIRIS, YOU FUCKING MULE,” he snapped as the dwarf-axe he hurled to the ground fell several feet to to Khiris’ left because Yin’s ugly spawn had his eyes squeezed shut. The descent wouldn’t hurt a dwarven weapon, but others would bend or snap if let to clatter onto the stones of the courtyard like that. Gris would have cursed him out further, but the perilous ground on which he was skillfully balanced twisted and heaved under him again. A growl rose form its bellows, rumbling up its throat as slow and building as a creeping wave; its great eyes slit again.

Gris’ old, aching knees perched him precariously on the belly of Lord Glaurung, his great, undulating expanse as slippery as the muscled sides of a snake and so large that even the smallest growl in his gullet tossed Gris around like he stood on billows of molten iron. Only the scales and ridges stuck to his hide gave Gris enough of a foothold for the very hard work he had taken on himself.

Someone had had the brilliant idea of having the most valuable member of the army lead it into the biggest push they had planned in a century. Which had gone well, overall, and they hadn’t lost Lord Glaurung in any of the several charges he had personally led, but most of his legs and some of his stomach were now lined with elven spears and arrows, dwarven axes, and human blades, and despite having so many wondrous abilities gifted unto him by his illustrious lineage, one thing Lord Galurung did not have was hands. Orcs had hands. So far, five or six orcs had been stomped, thrown, or flattened to an early grave, and now all of the rest of them were suddenly fucking cowards except for Gris, who had seen ten and three decades of the halls and workshops and courtyards of Angband, all of which involved Glaurung and his numerous descendants making demands of the little orcs forced to run around their feet, which might now culminate for him in the final and most ridiculous demand of Gris’ long and accomplished career: pulling spears out of Glaurung’s fucking dick.

One of the many aforementioned wondrous abilities that Glaurung’s aforementioned esteemed lineage (blood from the Masters mingled with whatever they put their weird divine dicks in) granted him was the power to directly insert his demands into the hollow spaces between Gris’ lungs and guts, where they vibrated like clanging shields. “You would benefit from minding yourself as you mind the dwarrow axes, smith.”

Again, Gris was not afraid to die today, nor fully against the idea. He planted his boots into the ridges of Glauring’s scales, felt the jolting pain in his knees, and screamed above it. “You mind your own manners if you want the axes out of your nerves! You want them out, I want raw steel, you figure out how to lie still and behave until I’m done or you go back to young-blood wool-for-brains cavalry grunts with the precision of a floundering carp on the block tearing up your skin as they wrench them out without me. Fuck,” he snarled, as his elbow hurt particularly hard through removing a curved elven sword from Glaurung’s stomach.

The dragon snarled again. The mere sound dug claws into Gris’ soft innards and Gris snarled back. He turned his head to glare down at Yin’s stupid brood again, but the boy was at least watching now, so Gris decided he would actually trust the idiot to pick up the fine blade as he tossed it down.

He gave it a quick, appraising look before he tossed it; stupid. Crafted thin for delicate elven hands, so thin it was nearly soft. Balance and fluidity compromised by lines of sparkling stones on the pommel that would throw light in the night, making any strategy requiring secrecy or swiftness foolish. Sub-par steel smelted with iron from the black soils of the east, where roots of vegetables sapped the strength of ores.

The thing was stock. Some of the respectable dwarven blades, small but strong, could be given to children; human swords were sometimes useful as they came, but the vast majority of elven blades could only be melted for stock and made into belt-buckles and door-hinges. Someone had put more effort carving their name in curling letters onto the hilt, silver embedded into steel, than they had actually making a working weapon. It was like watching a brooding boy use sword oil to shine up his hair. Who had given these barbarians tongs in the first place, and why had they been permitted to keep using them after showing out like this?

Khiris did catch it; at least, Gris didn’t hear it clattering onto the ground of the wide courtyard chosen as the only viable place for this unusual work. It was not any courtyard, the iron walks and rough circles of stone set outside of the halls around Angband for the purposes of public justice and tests of skill, but the wide, statue-lined, sparkling obsidian courtyard right outside of Angband itself, within his high stone walls. Glaurung had struggled in through the great gates and emptied it of its revelries in order to throw a fit right outside of the Halls of his Masters (and progenitors). Those Masters had snapped for ‘someone’ to go get all the weapons out of Glaurung and retired their revelries to the inside of the Fortress. The old fountain depicting the Master in His first form as Anarch Chaos, His true being before the Enemy suppressed it, was smashed. The great obsidian paving stones, brought from the old volcanoes of the north, were cracked or crushed. Several people died early deaths until Gris decided that, as usual, he was someone.

If he didn’t die, he would have a stock of fine foreign weapons like had hardly been seen before to do whatever he liked with, reuse hilts or handles, melt to stock, fold into the hearts of stronger, better blades. If he did die, by the Masters, he didn’t have to deal with Yin anymore.

Every once in a while, Gris almost capitulated to Yin’s requests for one more son. The two children that they had had, for as long as they both lived, had been skilled, respected commanders, always ready to leap into the fray. Too ready. But every time he nearly said the word (coaxed into the hall to drink by a melancholy, reminiscing Yin, remembering the weight of a child in his lap, seeing Yin’s downcast eyes, now lined with age, in the dim of the evening, with snow drifting outside the windows and fire catching the curve of his tusks), he recalled how Yin behaved while brooding.

Pits. No. Not again. He was too old. Other suckers could plant lesser sons in Yin’s gut. He was done. Yin could make dipshits like Khiris and Gris would teach those who could use their hands the skills they barely deserved in hope that something of the art would pass on; so far, only three had proven to have half a brain, so he sure hoped Khiris would spontaneously develop the rest.

“KHIRIS, THE BARROW. PUT THE ONES YOU ARE ALREADY HOLDING IN THE WHEELBARROW SO I CAN THROW YOU MORE. YOU SNAKE’S SWOLLEN CLOACA, I WILL POP YOUR EGGS OFF,” Gris shouted over the pain, looking over his shoulder on one side and reaching down with the other to wrench a human blade out of Glaurung’s stomach.

He paused to appraise it for a second. Now, that was a weapon. Its hilt was wrapped in strong leather, carefully evened out for the grip, just textured enough to serve soft human hands. The blade was straight and heavy, a little lighter than Gris would make but well-balanced. Its steel was a fine alloy, strong but forgiving, hardly scratched even by being wrenched past dragonscales. The pommel was understated and not compromised by some dumb son of a rabbit filling it up with his favorite pictures and scrawling his name on it just to assure that any time any of his clients was captured their enemies would know exactly where they came from and which houses were now empty and unguarded. Whatever human smith had plunked this in the hand of his warriors had done a good job and moved on to the next one, instead of thinking to himself, ‘I should spend three months making the same blade, because I want our legions forced to go into armed combat with mostly arrows and light maile.’ It hadn’t kept its wielder alive, but it didn't snap or bend while being wrenched out of Glaurung like many of its elven cousins had.

“KHIRIS, YOU FROG-LEGGED FOWL-FUCKER,” Gris bellowed as he tossed it away and his shoulder twinged with pain.

Khiris found the nerve to snap back. “STRONG WORDS FROM AN OLD CUCKOLD,” Gris heard from below.

To be honest, it was like a fly buzzing around his head. He hadn’t cared what anyone Khiris’ age thought of him even when he was Khiris’ age, making a dozen blades in a day and smashing the face of anyone who didn’t like him working on the anvil. Fist in hair, firm grip, and yank down. Finish with hammer if he really deserved it. That was something he missed about his youth. “YOUR BROOD-FATHER TELL YOU ALL ABOUT IT?” He yelled back down. “ASK HIM FOR DETAILS NEXT TIME, YOU FUCKING VIRGIN, YOU MIGHT LEARN SOMETHING.”

Gris maintained the jokes were funnier if you had, in fact, fucked the dam in question. He chuckled to himself as he leaned down to pluck something that was really in there.

Glaurung’s stomach tightened when Gris’ hand curled around its hilt. Gris paused. Out of the corner of his eye, he saw the dragon brace one of his claws against the pedestal of a statue. That one depicted the hard-armored, kneeling body of Lord Sauron, whose upraised arms gestured permanently toward the Master Himself.

There was a rumor that Sauron himself had fathered Glaurung.

His father was certainly one of the Lords, and his strength, size, and intelligence suggested it was a mighty one. The dragons were cagey about exact lines of descendancy, unlike orc-kin, who boasted of fathers of fathers. The eldest of the Masters had no Fathers, either spawned directly from Chaos Himself or, in the case of Chaos, beget of Himself. Their descendants followed suit, pretending they were fatherless or else referring to their progenitors only obliquely to seem more noble; also, perhaps, to obscure which ones had bred the animals on the other side of the dragons’ lineage. But the fact that Glaurung was allowed to lead other Masters and Lords into battle spoke what he did not deign to.

“Take care with your movements,” spoke Glaurung from inside Gris’ chest, as Khiris’ screaming voice faded as if he sank below waves.

“It’s in deep?” asked Gris roughly, his tired arm shaking.

“Too deep. It’s struck through the rough into the soft. If you pain me when you pull it, I will throw you off.”

“I suggest you find the courage to keep yourself still,” Gris responded roughly. “In case you’re too big to see, so far I’m the only person who’s got more than a few out of you without ripping a new hole into you. If you want me to keep doing it, you have to let me keep doing it.”

The dragon’s throat worked, and a fog of smoke leaked out from some of its bared teeth. “The size of my body and the size of my pain will overmaster you nonetheless.”

“Consider the size of your brain, old Master, and your discipline, provided you have some. I am taking this out, I am keeping it, and whether or not you throw me like a horse is up to you. Is it going to bleed?”

“I am sure it will, and the blood with burn you like forge-fire.”

“KHIRIS!” Gris bellowed. “GET A BUCKET, NOW!” Khiris scrambled to obey. “Then I’m keeping that, too,” he informed Glaurung. A dragon’s blood, when used to quench, made a hardened steel like nothing else. One was not supposed to have a Lord’s blood, but Gris had done many things he wasn’t supposed to in his time. Dragons were Lords that bled. Sins did not count if a Lord gave you permission. Gris wanted that blood.

Glaurung settled uncomfortably beneath him, his scales scraping on the stones below. His slit glare seemed to say that he was not bothered by Gris’ audacity because he was not convinced Gris would live through the next minute. Khiris brought the bucket and threw it up to Gris, and catching it from the air hurt so much that Gris bellowed down at him that he was the dumbest son of a whore he had ever met.

Khiris told him in return that Gris wouldn’t know, since he was too soft now even for a whore. Gris grumbled to himself as he made the inevitable choice to get down on one knee to get the blade out of the dragon. There was a solid chance he was about to hit the ground, so it didn’t matter that he couldn’t stand up again after kneeling.

He made preliminary judgments about the sword as he wrapped his fist around it again. Elven, likely made in the near north, given the dullness of its luster. That dullness was a comparatively good sign for elven weapons, as the smith had likely traded with the humans or had otherwise been given use of their superior alloys. (The elves seemed to prioritize how much light a metal threw in their decision-making about which ones to smith with, and it was so stupid. Gris was astonished that they were still at war with these idiots.) He could see only the hilt—even the pommel had been sucked into Glaurung’s flesh—but he could feel that it was attached to a relatively heavy blade and that the hilt was well-worn, used often. For a moment he wondered if it had been the blade of one of the elven warrior-watchers who walked and guarded the siege wall—and those could be called warriors—but they were usually equipped with arrow and spear, not sword.

Curious. Gris found himself rather interested in the blade itself, but there was only one way to get it. Cursing, he braced himself, readied the bucket, and pulled.

He pulled up at the angle through which Glaurung had been pierced. Reversing the wound came with the least chance of exacerbating it. After the initial resistance of the pommel, the blade slid out as easily as if the slit had seen a few in its time. Glaurung did complain, and did thrash, but Gris gripped a spear that was still stuck inside and just managed to ride out the convulsion. Not as much blood flowed as he hoped, but with some angling and steadying his shaking hand he did gather enough to mix with quenching oil to make a fine, brief generation of swords.

“There! How’s that, old Master? A fair exchange, and it turns out that you did not need to kill me.”

“A fair exchange?” huffed Glaurung, smoking more. “I only see you enriching yourself.”

“I can put it back in,” Gris offered, but he wasn’t even looking at the dragon now. He balanced the bucket so that he could squeeze the extra blood off of it with his fist and get a good look at the sword itself.

It was good. It was elven-made, too light and too subtle to be anything else, but from time to time he did find the product of an elven smith who appeared to be serious. It had also been used often and well, judging solely by the smoke-trails of wear on the blade, perfectly parallel to each other, marking the strokes of a well-trained arm. Its blade was long, heavy, straight, made to a sensibility that almost seemed between elven and human, practical but artful, not hindered by stones or designs or any other frippery. It was hindered in one thing, which was a solid knot of something tied around the hilt, now soaked and massed with the dragon’s blood and viscera.

It was something of fabric, sheep wool, a woven something. Gris narrowed his eyes as he squished blood out of it and tried to determine what he was looking at. It was decoration, a woven band of tightly knotted lines, made on a loom. Before Glaurung’s blood had dyed it it had likely been several lots, based on how its threads were pulled crossways against each other and even glistened differently while sodden. The patterns were minute, but Gris found with observation that he recognized it, because he had seen similar things on many human blades before.

“Human love-knots,” he said, momentarily astonished. There were tokens that human dams, which were kept in homes and forbidden from the field, gave to the sires who went to fight. But to have one here, on the blade of an elf—

“Warg shit, they’re fucking breeding each other now,” Gris wrenched his head back, appalled. “May I not live long enough to see the product of that union.”

“You shan’t, white-haired one,” informed the rumbling dragon beneath him. “Your years flee you like water in the palm.”

“Good riddance. Every one hurts more.” Gris considered the blood-soaked love-knot, and thought to himself of what it would be like to have Yin locked in a home, every time he went to battle, weaving armor. No wonder these fools kept losing wars. Halving their army, for what?

“Do you know, old smith, that it was the will of Eru rather that you might have unending life, not the dwindling you have been crushed with?”

“The will of who?” Gris asked.

“He is among the Eldest of the Masters; to invoke his name might kill you as you stood. Care to try?”

“He must stay in the Fortress with the harems and banquets like the Great Masters instead of coming outside, because I’ve never heard of him.” How would Yin look with a love-knot in his hair, or Gris with it wound around sword or hammer?

Like an old fool, that was how.

“The will of Eru and His Song and all great things will be forever unknown to you, you creature of the mud of this earth. Your lot is to work until your limbs break, but you all scrabble for life like it is as precious as gold to you. Why?”

“Do you think I can answer any questions that you cannot?” Gris returned, a quick response, a correct response, but even as he said it he did wonder why he was being asked. Masters would taunt them with questions like this, but the only real answer was ignorance. Anything else was punished.

Glaurung was no longer seeping smoke, and indeed lay back on the shattered courtyard looking only tired. Perhaps that blade has been dealing him the majority of the pain. “What do you live for, crawling creature?”

The question had its answer in Gris’ heart. The craft. To make another blade or breastplate or wagon axle again and be pleased with it again. It also had a correct answer: “To serve.”

Glaurung’s great body pulsed once, a hiccup in its stomach, perhaps a laugh. Gris slowly, slowly began to straighten up, a process of pain, to throw the sword to down to his stupid apprentice. When he looked down to see the upturned aggravation and anger in Khiris’ face, he saw in his displeasure his resemblance to his brood-father, melancholy Yin.

His knees hurt like they were being stabbed with every heartbeat upon standing. Hefting the sword behind his head, he shouted, “WHEN I DIE, IT WILL BE IN THE ACT OF PUTTING ONE MORE BASTARD INTO YOUR WHORE DAM, AND MAY MY HEART TAKE ME IN THAT MOMENT.”

--

Original Note:

I've said this I think about every protagonist of each chapter of this series, but I love Gris more than life.

‘Anarch Chaos’ is a pull right from Paradise Lost, in which the figure of Christian Satan, on his way up from Hell after his banishment, discovers the court of Classic Mythological Embodied Chaos, who is referred to as ‘the Anarch Old’ at one point. I love that moment. Milton was an inveterate classicist that couldn’t keep some old Greek figures out of his thoroughly puritan Christian Mythos. He was a complicated man. Satan defers to old Chaos and begs his aid, thus Sauron’s accompanying kneeling statue.

Here, Morgoth mythologies Himself, claiming to have been once the first figure of eternal Chaos before the ‘Enemy’ (here Manwe) split him into several beings and degenerated him into what he is now. (He never mentions Eru, since it doesn't do for his mythology for anyone stronger than him to exist. As for the hypocrisy of an authoritarian calling himself Anarch, I Know, Right?) Of course, orcs are supposed to believe that Morgoth is weak enough that he has to cower in his fortress, hiding from elves and maiar, and simultaneously secretly the strongest thing in the universe; thus ever fascists.